There’s a popular joke amongst musicians, cracked during slow moments in rehearsal and paired with a good dig at the violas (or four).

Knock, knock.

Who’s there?

Knock, knock.

Who’s there?

Knock, knock.

Who’s there?

Philip Glass.

Talk about a groaner. Yet the punchline speaks to the indelible mark Philip Glass (A.B. ’56) and his repetitive, hypnotic music have left on the collective consciousness. Less than forty years ago, Glass’s works were jeered at the Theatre des Champs-Elysées, the same venue in which Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring was rioted into submission. Today, there is little in music as instantly recognizable as Glass’s scores, which have graced everything from film to stage to television commercials.

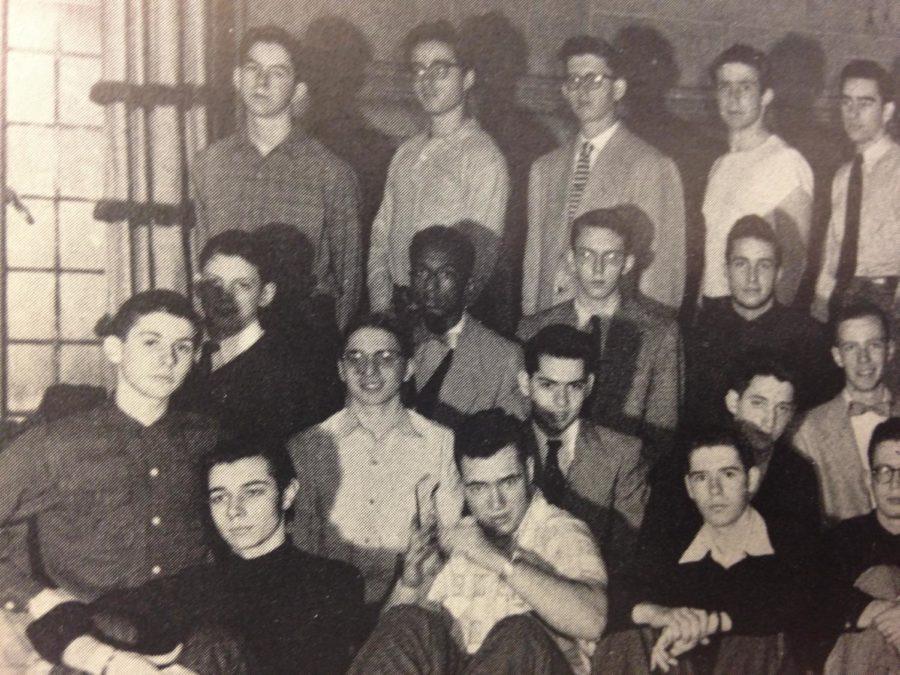

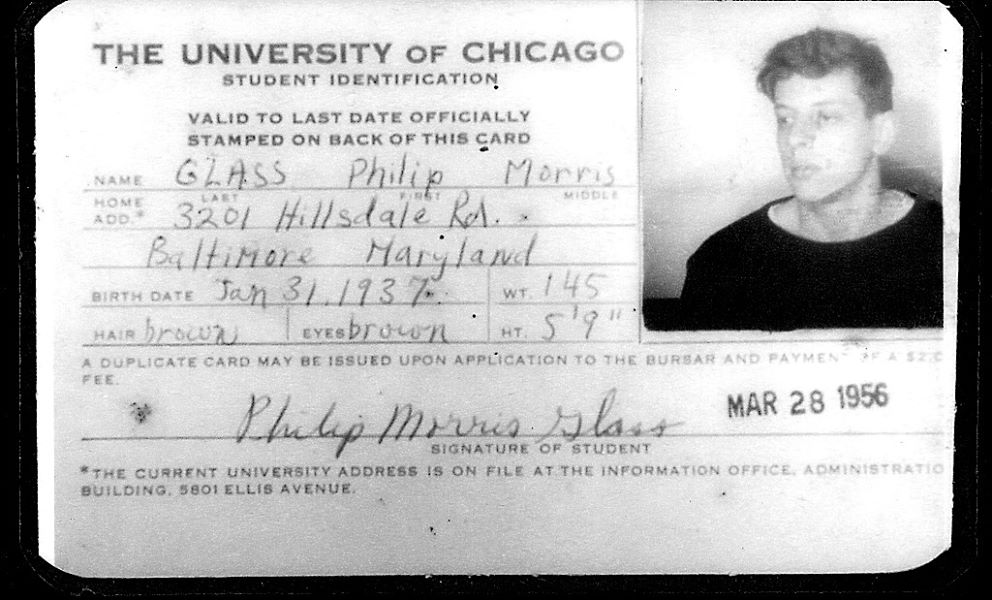

Whether beguiled or bewildered by Glass’s work, one thing is incontestable: He is one of the artistic giants of our generation and one of the University’s most famous alumni. In a press conference last Thursday, Glass asserted that his “most formative years” were spent at the University of Chicago, whose early entrance program offered him a ticket out of Baltimore when he was only 15. Now 79, Glass returned to campus last week for a three-day residency as a Presidential Arts Fellow—his first such residency at his alma mater.

The residency began Wednesday with a screening of director Paul Schrader’s kaleidoscopic Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985), set to Glass’s scintillating, canvas-like score. The screening was followed by a discussion with Associate Professor of Music Berthold Hoeckner, during which Glass shed insight into his creative process and preparation for biographical projects like Mishima (spoiler: lots of reading).

Events continued on Thursday, beginning with a private masterclass for composition students and ending with a public conversation between Glass and Professor of Composition Augusta Read Thomas. The conversation was at turns intriguing (“With every new style of music, there’s a new performance practice that goes with it—if not, then it’s not new music”) and amusing (following an excerpt of Music in Fifths: “That goes on for about 20 minutes”).

The residency culminated in a sprawling performance of Glass’s complete piano études at Mandel Hall on Friday. Glass himself was joined by four other pianists: Aaron Diehl, Lisa Kaplan, Maki Namekawa, and Timo Andres. The performances were committed and the performers idiosyncratic; Diehl’s jazziness, Kaplan’s vigor, Namekawa’s emotional breadth, and Andres’s vibrancy refracted the 20 études into distinct new hues.

During Wednesday’s post-screening discussion, Glass asserted that a work alone cannot create art, but an individual’s interaction with the work can. As Glass’s co-performers nudged him forward to take his final bow at Mandel—the sheer volume of applause drowned out only by the music still lodged in our ears—his words had never seemed so salient.

Uncommon Interview: Composer Philip Glass on His Music, Alma Mater

On the second day of his residency, Philip Glass generously sat down with second-years Hannah Edgar (MAROON Arts Editor) and Daphne Maeglin (WHPK, UChicago Music Department) in the Logan Center. The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Hannah Edgar: It’s 2016, 60 years since you graduated from the University of Chicago. You graduated in 1956—

Philip Glass: Oh my God, I did…Is that possible?

HE: I don’t know, you tell me! [Laughter] What’s it like being back?

PG: Well, I can see my dormitory—[points out the window at Burton-Judson Courts]—and that was the library, Harper, right over there. So [the University’s] gotten a lot bigger, but I’ve also kept in touch; I’ve been back through a few times.

My impression is that there’s a special spirit to the University of Chicago, and there are so many great people coming out of it. There seems to be a real connection with the past and the present here, so it feels like the same place to me. […] But I think what’s impressive is the reputation and the presence of the University in American life, in general—it’s still very strong, very present, and that has not diminished at all. This was always a very powerful place to be.

Daphne Maeglin: You talk in your memoir about how you always knew you wanted to be a musician, even as a student here.

PG: Well, that developed while I was here. I was studying music at Harper Library, because there wasn’t any music school here. This building [the Logan Center] wasn’t here. There was a little building—it was just a house—that one teacher, Grosvenor Cooper, lived in. He was the only music teacher at the University at the time.

So I had to leave to study music. I could’ve gone to the Near North Side to study, [where] there were places to study. But if I left the South Side, I thought I might as well go to New York. But I’m from Baltimore, not from here.

It’s hard for people to leave Chicago. Sometimes they just don’t do it. But if you’re not from Chicago—I was here four or five years—you could tear myself away. My roots finally [took hold] in New York, which for a musician is a very good place to be. But Chicago is too.

DM: In what ways was Chicago a good bridge between Baltimore and New York?

PG: Well, the place I’m playing, Mandel Hall, was where we [students] heard concert music. From Big Bill Broonzy to the Budapest Quartet, everyone came through there. But then in the neighborhood, here in Cottage Grove, I heard Billie Holiday, and down on 55th Street was the Beehive, where I heard Bud Powell. It was not connected to the school, but the school was embedded in this area where there was music going on.

There was also music downtown in the Loop. Fritz Reiner was the conductor of the Chicago Symphony—fantastic conductor. Now, if you remember, I was there in 1952, ’53, and he was playing pieces that Bartók wrote right before he died. I mean, they were new pieces, and he knew them because he knew Bartók. The orchestra played great, but I think the audiences were not totally prepared for it.

HE: Speaking of unprepared audiences, you, too, received a lot of pushback against your music early in your career. Do you feel like that was the result of some sort of “musical establishment?”

PG: I didn’t think of it that way. When I wanted to go to music school, I decided to go to what I thought was the best school in America, so I went to Juilliard. But I had no idea how to get into the school. In fact, for the first year there, I wasn’t even a matriculated student; I could take courses, but I didn’t pass the entrance exam for a year. When I left there, my music began to change very radically.

But I didn’t think of it as a musical establishment—I had a different thought. I was very interested in independence, and not being part of somebody else’s imagination. The opinions that came from academics, and even from my own music school—I had no trouble ignoring them. In fact, I like the fact that I was rejected, because it meant that I was left alone. I was working downtown, I started an ensemble, I made a life with off-Broadway theater people downtown… I didn’t belong to any musical establishment at all. In fact, I was 72 when I was offered my first teaching job! [Laughs] And I thought, y’know, it’s a little late.

And I discovered another interesting thing. The music establishment was like everything else: The people who were very hostile and threatened by the music, basically they died. Actually, what happens is that no one changes their mind; they just die! Then finally, the people that are teaching there—oh, they’re 30 and 40—they’re younger than me!

I even find it still a little surprising because I’m kind of used to not being in the schools. But this [residency] is different because I’m an alumnus and have a special place here, I think.

DM: This Tuesday, the Chicago Tribune wrote that you’ve “bridged the worlds of high and low culture in ways few composers of any era have achieved.” Do you believe there’s a distinction between high art and low art?

PG: Well, of course [not]. I have to believe that. I’ve done everything in music—I’ve done commercials, I’ve written film scores. I’m doing a benefit concert on Monday for the Tibet House in New York, and Gogol Bordello and Iggy Pop are on the program. I’m the organizer of the concert; I invited them! I enjoy being a fellow traveler in other people’s worlds, and I’ve learned a lot from that, too.

I did two symphonies with David Bowie and Brian Eno; people say, “Why’d you do that?”, but composers always did that! Musicians often would take folk music and put it into their symphonies. So, what’s the difference? I’d say, “Well, I picked those guys because they were the most talented guys that were around.” Why wouldn’t I do it?

HE: You mentioned during last night’s screening that you’re working on incidental music for The Crucible. And next year, you turn 80. What’s next?

PG: Well, I’ve got a new piece I’m doing with James Turrell, an artist who works with light, and the dancer Lucinda Childs. I’m doing another piece with Brian Greene, a string theory physicist, who’s written a story called Icarus on the Edge of Time, and I did the first part of it about three years ago. That’ll open in November. Then I have a new symphony—which I may have started already, I’m not sure—that’s for my 80th birthday, which is January 31.

The nice thing about musicians is that we’re very active. I still like to play the piano, and Ravi Shankar was I think 93 and still playing. I heard him playing when he was 91. People can hang around for a long time.

I also like to keep writing. I like writing, and my musical thinking is still evolving. It’s either evolving or devolving; it depends on who you ask! [Laughs] It’s definitely changing.

DM: When you were young, the older generation wasn’t accepting of your more tonal music. Do you think today’s music is breaking ground in a similar way?

PG: This is a very rich time for new music, and I’ll tell you why. In the ’50s and ’60s, during the McCarthy years, we had Allen Ginsberg and free jazz and all kinds of things. What I’ve noticed is that when this country [has] terrible problems, the arts go nuts. They go great! And the same thing is happening now. [Even though] it looks like the country’s going to the dogs, at the same time, there’s almost a renaissance of new music, theater, and dance which is beautiful. We almost haven’t had a period like that in 40 years or so, and it’s happening right now. [. . .]

There are more radical changes happening right around us, and I find that I love to listen to this music because it’s music I never would have thought of. And what could be better than that?