The distribution of wealth in our country has become a big talking point for many of the candidates on the presidential campaign trail. Those on the right contend that the inequalities are not as bad as they appear, and that having such large class disparities is ultimately good for economic progress—the wealthy create jobs, the less fortunate take those jobs, and everyone is better off. Those on the left say that class inequality is hindering progress, growth, and opportunity, and that the top earners should pay more in taxes to ensure that the bottom socioeconomic classes have the potential to make their way to the top. Left-leaning political figures, then, are aiming for a more equal society. What both sides agree on is that there is a fundamental divide in American society. The differences come in how they view the solution, or rather, if this divide even represents a problem.

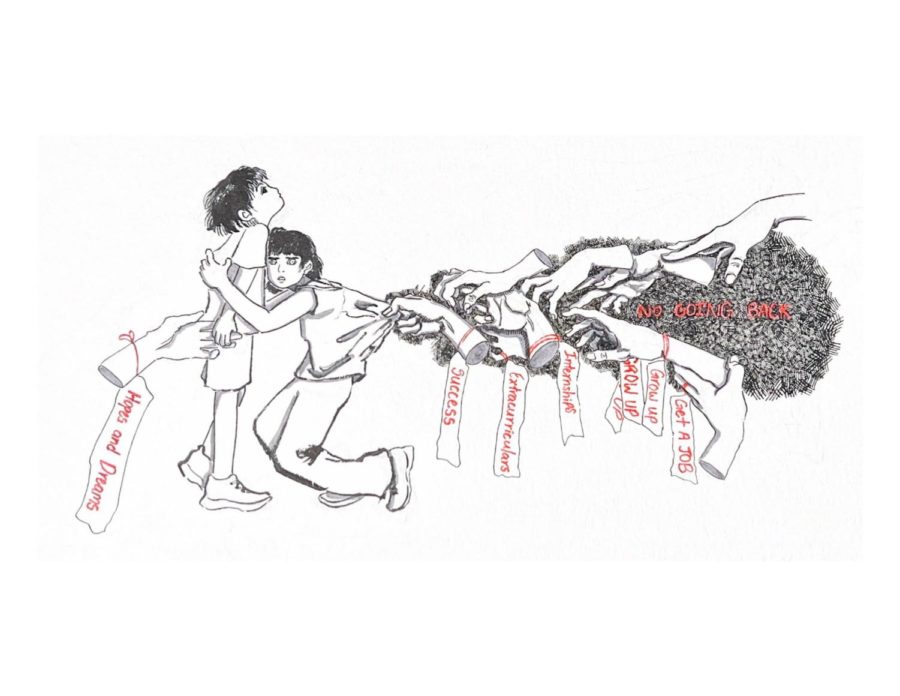

Issues of socioeconomic class bring about some of the most challenging forms of discrimination in American society, and, when combined with issues of race, gender, and other biographical forms of discrimination, can be absolutely paralyzing to a person’s ability to improve their economic and social standing.

But there is a fundamental issue that makes tackling socioeconomic discrimination difficult: socioeconomic class is not an immediately obvious part of a person’s identity. Race, gender, and even sexual orientation can be apparent, or at the very least, can be vocalized by an individual. It is far easier to identify with a racial group or gender than it is to identify as impoverished, middle class, or even rich. The distinctions between these groups aren’t always clear, and people often miscategorize themselves. Besides that, there is a commonly held belief that people who are wealthy deserve to be, and those who are not simply haven’t worked hard enough. This is why class-based movements have been unable to make real and lasting change in the American political landscape.

The markers of socioeconomic class are difficult to recognize in other people, let alone in oneself. Even with serious self-reflection, understanding one’s place on the socioeconomic ladder can be next to impossible. A person may have luxurious or expensive consumer goods—e.g. cars, televisions, appliances, and clothing—but still not be among the upper socioeconomic classes. These goods have become cheaper and cheaper as time has gone on, while the prices of necessary goods like food and housing have continued to increase in relation to income. Someone who is in the bottom socioeconomic classes may now be able to afford a nicer television or car, but be less able to feed their family. Outward displays of wealth and affluence, therefore, are less meaningful than they were in the past. A person may, as a result, assume that they are in a higher socioeconomic class than they are, and also believe that those around them are doing well. This makes organizing a political movement even more difficult—when nobody is really sure of their position, how can they feel empowered to change it?

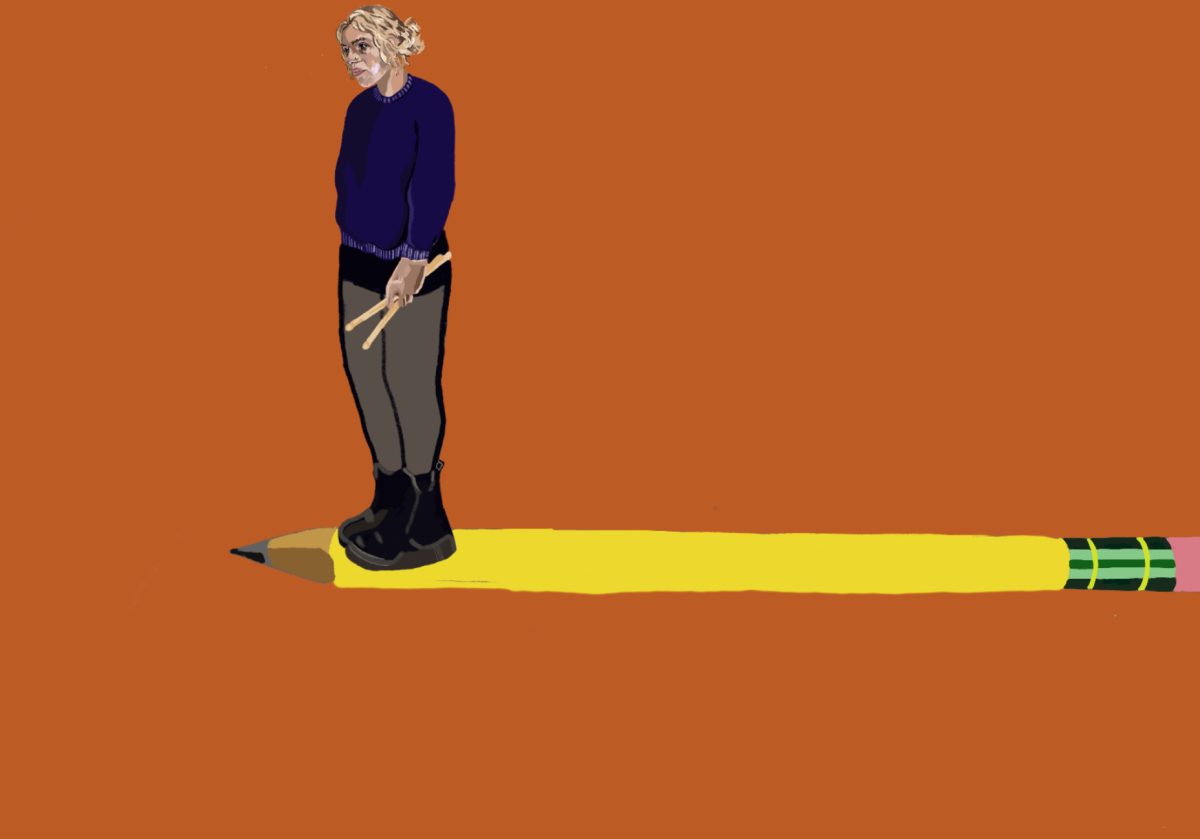

A more insidious and upsetting problem, though, is the belief that those who have money simply (and admirably) did everything in their power to achieve that wealth. They are viewed as uniquely able and inherently deserving of their higher status. This view presupposes that American society is a pure meritocracy, and that this meritocracy is fair. However, American society is anything but fair. It is the illusion of the American Dream—in which everybody has a fair chance, and with enough hard work, their success is guaranteed—that has deluded many people into believing that they are simply unsuccessful people. They don’t take into account the many ways that American society had disadvantaged them, or the ways “successful” people were given a head start.

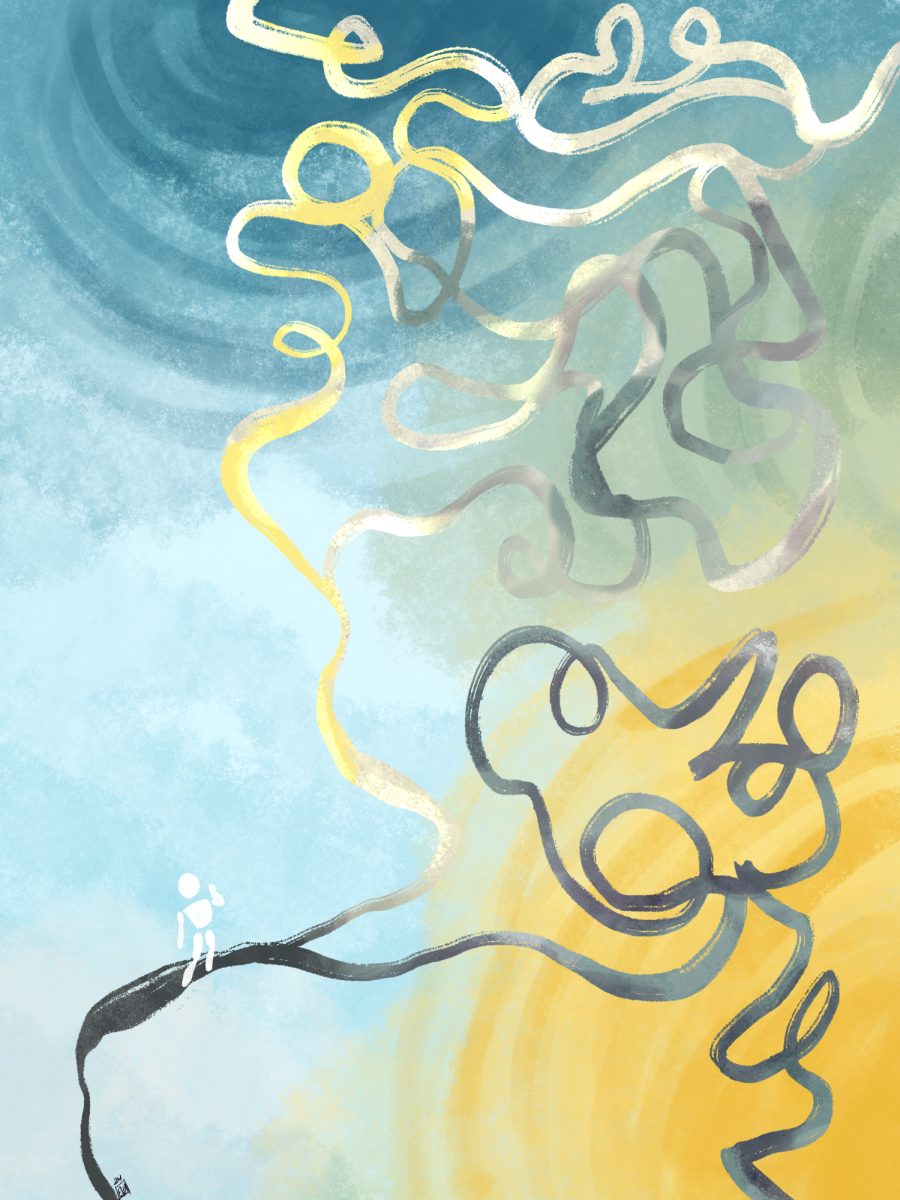

As diverse as issues of race, gender, and other discriminatory biographical details may be—something unites these groups. Members of each of these groups face socioeconomic discrimination. By providing metrics to better assess one’s own socioeconomic status in relation to others, a new awareness of class-based identity could unite people across a multitude of demographic groups and identities. By uniting around issues of socioeconomic discrimination, these groups will be able to strengthen their political voice to effect real change. So long as America remains a money-based society, the need for economic fairness will remain a politically and socially important issue, and as such, it will remain important for these groups to understand and organize themselves to overcome the forms of economic injustice that they face.

Andrew Nicotra Reilly is a second-year in the College majoring in economics and political science.